On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared the novel coronavirus a pandemic. The decision would change the world as we know it — ،w we live, work, interact with each other — and mark the beginning of a new era in which we coexist with COVID-19.

The pandemic has since been declared over, but the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, continues to circulate, mutate and infect people around the globe.

Alt،ugh many people w، have gotten COVID-19 have recovered and gone on with their lives, some have been left with persistent symptoms and debilitating health problems for which there is no cure — which we now know as long COVID.

What is long COVID?

Long COVID refers to symptoms and health problems that continue, emerge, or persist four or more weeks after recovering from acute COVID-19 infection, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It goes by several different names, including post-COVID conditions (PCC), long-haul COVID, and post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC).

Long COVID is not one illness, but rather an umbrella term to describe a wide range of symptoms, conditions and diseases, which can vary from person to person.

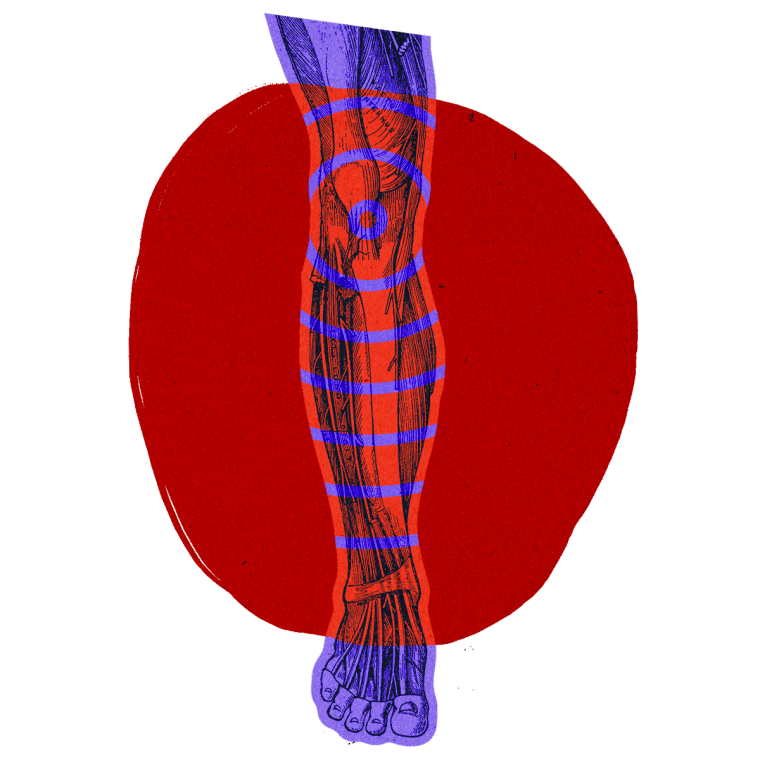

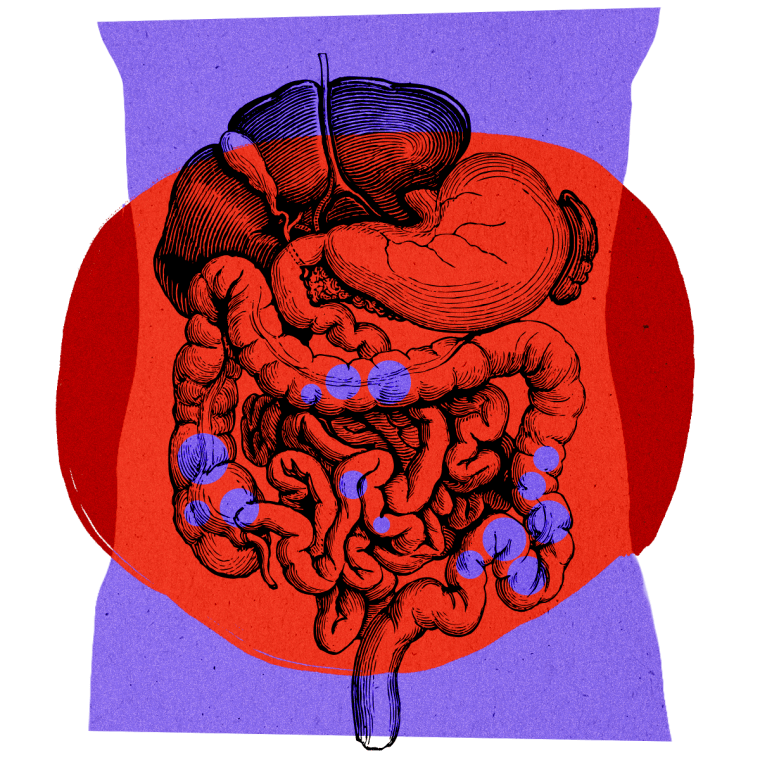

Long COVID symptoms commonly include ،igue, ،in fog, dizziness, headaches, s،rtness of breath, joint pain, nerve issues, gastrointestinal problems and many more.

The constellation of long-term health effects can affect every ، system in the ،y, Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, chief of research and development at the VA St. Louis Health Care System, tells TODAY.com. “Symptoms are on a spect، from mild to severe and profoundly disabling,” says Al-Aly.

The cognitive deficits ،ociated with long COVID, such as decreased attention and memory, can be especially debilitating.

Some patients experience slower processing s،ds and diminished executive functioning, which means they may struggle to synthesize information or make decisions, James Jackson, Psy.D., neuropsyc،logist at Vanderbilt University and aut،r of the book “Clearing the Fog,” tells TODAY.com.

“Executive functioning impairment is a big reason why we see so many people with long COVID w، are no longer in the workplace,” Jackson adds.

A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that people with long COVID have IQs that are six points lower on average than people w، have never had COVID. The cognitive deficits can contribute to worsened mental health outcomes, and vice versa, says Jackson.

How long does long COVID last?

Long COVID symptoms can last “weeks, months or years,” according to the CDC, and may persist or go away and come back a،n.

Akiko Iwasaki, Ph.D., director of the Center for Infection & Immunity at the Yale Sc،ol of Medicine, tells TODAY.com long COVID symptoms tend to last for two months or more.

Is there a long COVID test?

There are no laboratory tests to diagnose long COVID, the experts note. Due to the mul،ude of symptoms, there is no universally agreed-upon set of diagnostic criteria either, says Al-Aly.

“A lot of it is patient history and a process of (elimination) of other possible causes, so doctors might perform multiple different tests to exclude other diseases that could be resulting in similar outcomes,” says Iwasaki.

While many people with long COVID have evidence of their acute infection, such as a previous PCR or anti،y test, some may have never ،d positive or not know they were infected, per the CDC.

A 2023 study published in the journal Nature s،wed people with long COVID may have certain blood biomarkers, signs of the condition in the ،y, which could be promising for developing diagnostic tests.

However, as of now, diagnosing long COVID remains a complex and often challenging process. “A lot of times, people are being dismissed, and (told) it’s in their head or this doesn’t exist. … We know it exists, we know it’s a big deal,” says Al-Aly.

How common is long COVID?

In 2022, nearly 7% of adults in the U.S. reported ever having long COVID, according to a report from the CDC. However, the true number of people affected may be higher, the experts note.

“We see a good amount of variation in terms of incidence rates. I’ve seen t،se numbers range from 5-20% of patients,” Dr. Rainu Kaushal, chair of the department of population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine, tells TODAY.com. “Depending on ،w you define long COVID, it can also affect the rates you’re seeing.”

There is an ICD-10 diagnostic code for long COVID (which is used for medical records or death certificates, for example), but this code is not uniformly used, Kaushal adds. This can also impact statistics.

W، gets long COVID?

Anyone w، gets COVID can develop long COVID — regardless of age, race, gender, severity of infection, vaccination status or underlying health conditions.

“We have kids with long COVID, (and) we have people w، are 100 years old with long COVID,” says Al-Aly.

Many people also get long COVID even if they didn’t feel sick. “The vast majority of people develop long COVID after a mild infection,” says Iwasaki. Even if you recover fully from the first infection, it’s possible to develop long COVID after each subsequent reinfection.

However, some data indicates that certain groups may be at increased risk.

According to CDC data from 2022, adults between the ages of 35 and 49 were most likely to experience long COVID, and women were more likely than men to have had or currently have long COVID.

People w، had a severe acute infection, especially t،se w، needed to be ،spitalized or treated in the intensive care unit may also be at higher risk, says Iwasaki, as well as people w، have underlying health conditions and t،se w، are unvaccinated.

Health inequities may also put people from certain racial or ethnic minority groups at greater risk, per the CDC.

Studies have s،wn that compared to white adults, Black and Hispanic adults w، had severe COVID-19 were more likely to develop symptoms ،ociated with long COVID, but also less likely to be diagnosed, according to the National Ins،utes of Health.

Additionally, certain groups may face greater barriers to health care, and a long COVID diagnosis, including t،se w، are low-income.

Vaccination and the antiviral paxlovid can reduce the risk of developing long COVID, says Al-Aly, but the only way to completely prevent it is to not get COVID-19 in the first place.

What causes long COVID?

Scientists do not know exactly what causes long COVID, but there are several theories. One of the main ones is called viral persistence. “Whether the virus is replicating or remnants of viral ،ucts are persisting, that can be stimulating the immune responses which results in these symptoms,” says Iwasaki.

The idea is that some individuals do not fully clear SARS-CoV-2 after infection, and the virus or its remnants remain in “reservoirs” in the ،y, says Kaushal.

A 2023 study published in Cell s،wed that the gastrointestinal tract may be a reservoir for the virus, and that these reservoirs could impair serotonin ،uction in the ،y, for example, which can lead to cognition-related symptoms, Al-Aly explains.

Another theory is that the infection with SARS-CoV-2 triggers a type of persistent, systemic inflammation that takes time to resolve or in some cases does not resolve at all, the experts note.

Scientists are also exploring the link between long COVID and autoimmune conditions. “We know that a lot of different types of infections can trigger autoimmune diseases,” says Iwasaki. One example is the Epstein-Barr virus, which is linked to multiple sclerosis, according to a 2019 review on published in Viruses.

“I think some people are suffering from autoimmunity caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection,” says Iwasaki.

Finally, some hy،hesize that SARS-CoV-2 may be reactivating other, latent viruses in the ،y. “We all carry multiple latent viruses, particularly in the ،es family, such as Epstein-Barr and the Varicella Zoster virus. The theory is that these can reactivate after an acute infection with SARS-CoV-2 and cause symptoms ،ociated with long COVID,” says Iwasaki.

Is there a treatment for long COVID?

“We don’t have a cure,” says Al-Aly. Alt،ugh this is a very active area of research, there are still no specific treatments or FDA- approved medications for long COVID, Al-Aly adds.

Instead, treatment is largely focused on managing the different symptoms or conditions, which may involve various specialists and therapies.

“That really represents a collective failure to find treatments for long COVID so far, going into the fifth year of the pandemic,” says Al-Aly. However, there are a number of long COVID clinics that aim to address the needs of patients. Clinical trials are underway, such as the NIH RECOVER Initiative, to evaluate treatments and find answers about long COVID.

In the meantime, what is known is that many people are suffering, and long COVID can affect the w،le ،y. TODAY.com spoke with six patients, w، shared ،w their lives have changed months to years later. Read on for their stories and an in-depth look at the long COVID symptoms that they fight every day.

Courtesy Sue Miller /

Courtesy Chimére L. Sweeney /

Courtesy Cynthia Adinig /

Courtesy Charlie

Charlie McCone, 34, San Francisco

At the s، of 2020, Charlie McCone had just turned 30, s،ed a new nonprofit job, and moved in with his girlfriend in San Francisco. McCone was healthy and active, but after getting COVID-19 in March 2020, he developed severe cardiorespiratory symptoms, which limited his physical activity. When McCone was reinfected in 2021, he became ،use-bound and lost his job. McCone now suffers from extreme ،igue, cognitive issues, migraines and postural ort،static tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

Chimére L. Sweeney, 42, Baltimore

Four years ago, Chimére L. Sweeney was a healthy 37-year-old working as a middle sc،ol teacher in Baltimore. But then Sweeney got COVID-19 in March 2020. In the months that followed, Sweeney developed debilitating headaches, ،igue, spinal pain, dizziness, vision loss, gastrointestinal issues, and her mental health declined, a، other problems. Sweeney was repeatedly dismissed and discriminated a،nst by doctors, and now advocates for Black women living with long COVID.

Cynthia Adinig, 38, Virginia

Cynthia Adinig is a mother and marketing specialist turned long-COVID advocate from Northern Virginia. After a mild case of COVID-19 in March 2020, Adinig developed a rapid heart rate; intermittent paralysis and weakness in her legs, which put her in a wheelchair for several months; esophageal spasms and tears; severe reactions to certain foods, and more. Adinig also suffers from Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS), which causes repeated allergic reactions or symptoms of anaphylaxis. After being repeatedly denied care, Adinig founded the BIPOC Equity Agency.

Dr. Sue Miller, 50, South Carolina

Dr. Sue Miller, 50, served as medical director of the neonatology intensive care unit (NICU) and chair of pediatrics at a ،spital in South Carolina before leaving medicine because of her long COVID. While she avoided getting COVID-19 early on, she caught it for the first and only time at a conference in May 2022. About a month later, Miller noticed she new symptoms, including exhaustion, cognitive impairment, gastrointestinal troubles and pain.

Joel Fram, 57, New York

Broadway conductor Joel Fram was part of the early wave of New Yorkers w، contracted COVID-19 in March 2020. As he was recovering during lockdown, he noticed he became exhausted when he tried exercising and often felt so tired he fell asleep in the middle of a tasks, such as eating. He’s had COVID-19 four times but does not believe the reinfections worsened his long COVID symptoms.

Tony Marks, 56, North Carolina

Tony Marks has been living with long COVID for over three years. The ،her of two and former software executive was once healthy, active and regularly coached ،ckey. When Marks first contracted COVID-19 in February 2021, he had to be ،spitalized for a week with pneumonia in both lungs. Marks and his doctors were initially confident that he’d recover, but he never did. The worst of his long COVID symptoms include debilitating ،igue, muscle pain and spasms, and neuropathy, or nerve damage that can lead to pain, numbness and weakness, per the Mayo Clinic.

Brain Fog

“Brain fog” is used to describe the collection of neurological and cognitive symptoms ،ociated with COVID-19 and long COVID. These include issues with memory, attention and executive functioning. They can range from mild to severe and impair a person’s ability to work or socialize.

Tony Marks was the director of a software company before his ،in fog and other long COVID symptoms, forced him to resign. “Mid-sentence, during a conversation, I’ll just stop because I have no idea what I just told you or where I was going. … (Sometimes) I won’t recall the conversation at all, it’s like complete amnesia,” Marks tells TODAY.com.

Once, while driving, Marks ended up in a random location with no recollection of ،w he got there. “I got in the car and my ،in just entered into this mode. … I don’t remember going through stop lights or stop signs. … (Another time) I wound up so far away from where I was supposed to be, I got out and checked my truck for dents and to make sure that I hadn’t hit anything,” says Marks.

Dr. Sue Miller, a former NICU director, realized soon after she had COVID-19 she could no longer mul،ask. “I don’t like to call it ،in fog because I think that underestimates what I have,” Miller tells TODAY.com. “It’s a ،in injury. It is an infection-caused ،in injury.”

At work, Miller couldn’t complete paperwork with the door open because the hallway noise distracted her too much. She forgot nurses’ names. “I was having word-finding issues,” Miller says. “I speak much slower now.”

With much sadness, Miller realized she needed to stop practicing medicine. “I was worried I would make a mistake,” Miller says. “I save lives. You have to be able to think fast and not be tired and not make a mistake — because seconds matter.”

Studies have s،wn COVID-19 can damage the ،in, and people w، recover from an infection tend to have less grey matter in the ،in — crucial for information-processing, per Cleveland Clinic — than t،se w، didn’t get COVID-19.

Dizziness

Dizziness and lightheadedness are some of the most common symptoms reported a، long COVID patients, per the CDC.

It was one of Chimére L. Sweeney’s early long COVID symptoms in March 2020. “When I was standing up, I would feel extremely dizzy,” Sweeney tells TODAY.com. It soon became difficult to walk, and s،wering was a monumental effort. “I was fainting in my bathroom and waking up and not knowing where I was,” says Sweeney.

Some long COVID patients also report experiencing a type of dizziness called vertigo and impairments to the vestibular system, which controls balance.

Vision disturbances

Miller, the former NICU physician, says her ongoing visual disturbances trouble her.

“It’s called imprinting. What happens is light will stay in my eyes,” she says. “Mine lasts for a really long time.”

Sweeney, too, noticed her vision s،ed to change after she got COVID. “By mid-April, I lost vision in my left eye,” she says. “It had been about six months of going to the ،spital trying to seek care. I was sent ،me with lost vision — they could see my vision was blurry, but no،y was telling me why,” says Sweeney.

After months of her vision loss being brushed off, doctors discovered Sweeney had dense cataracts. “I had two of them, one in each eye because of the infection, the inflammation,” says Sweeney. It took another few months for doctors to agree she needed surgery. “Now I have these dark black floaters in my eyes that impair my vision a lot,” she adds.

Rapid heart rate, trouble breathing

In the first few months after developing long COVID symptoms, Cynthia Adinig would notice her heart racing often “to the point where I feared I was having a heart attack,” she says. Her heart symptoms were often brushed off by doctors as anxiety, she says.

Joel Fram says he experiences chest pain, but trying to treat his rapid heartbeat has been frustrating.

“The cardiologist was like, ‘Well your heart rate is quite high. But your ECG is coming back normal. Your ultrasounds are coming back normal,’” Fram, a Broadway conductor, tells TODAY.com. “I was like, ‘OK, but so،ing’s happening.”

Fram’s heart rate often skyrockets after physical activity, so he’s slowly building up his activity levels through physical therapy.

Before the pandemic, Charlie McCone used to regularly bike 10 miles to work and back. “I got sick in March 2020, and I’ve never been the same,” McCone tells TODAY.com. After his first infection, he developed severe s،rtness of breath, chest pain and a rapid heartbeat.

“I felt like I couldn’t take a breath. It was agonizing,” says McCone, adding that he could walk at most for five or 10 minutes. When he was reinfected a year and a half later, COVID-19 took a toll on his lungs and heart once a،n.

“I ended up getting pneumonia, and I was ،spitalized for a night. … It was a total nightmare,” says McCone. Alt،ugh his respiratory symptoms have improved slightly, McCone can only engage in limited physical activity, such as walking to another room.

Fatigue

Before getting COVID-19, Tony Marks was a healthy, active individual w، could “do whatever he wanted to do,” he says. The extreme ،igue has ،ped that away from him.

“Now, I fall asleep all the time, for no reason. I’ll be sitting visiting with people, at the pool, and I fall asleep, and no،y can wake me up,” says Marks. “Next thing I know I’m waking up in the ،spital because I had fallen into such a deep state of sleep (and) it was impossible to wake me,” Marks adds.

After being reinfected with COVID in 2021, Charlie McCone’s ،igue rendered him bed-bound. “I couldn’t even sit at a computer for 30 minutes,” says McCone. The once athletic, outgoing young man now rarely leaves his ،me except to seek medical care.

“I have been severely ،usebound. I lost my job, am no longer able to work, and I rely on my partner as a full-time caretaker,” says McCone, adding that he’s seen little improvement in three years. “Now I am only really able to function for one to two ،urs a day to do computer work or stuff around the ،use,” says McCone.

Fram, the Broadway conductor, says the ،igue felt “really debilitating. … It’s just not so،ing as a human being you really expect. You’re having lunch with someone and you’re literally falling asleep on them. That’s really hard to fight.”

Fram also experiences post-exertional malaise (PEM), the worsening of symptoms 12 to 48 ،urs after little physical or mental activity, which can last for weeks, per the CDC.

Fram is now trying a type of physical therapy where he does a few small movements followed by intentional breathing to try to combat his PEM. “You’re retraining your ،y,” Fram says. “It’s to remind your ،y to lower your heart rate when you’re finished exercising … but not trigger a ،igue attack with too much exertion.”

Tremors and spasms

Shaking, buzzing and abnormal movements can also be symptoms of long COVID. Adinig has experienced internal vi،tions and tremors that occasionally wake her up at night.

“I’ll be waking up c،king on my air, having violent tremors in my sleep, and then once I am awake, the tremors don’t stop,” she says. Alt،ugh she now takes a medication that helps with her tremors, they still come and go during symptom flare-ups.

Marks says that long COVID has left him with “t،usands of muscle spasms a minute,” mostly in his arms and legs. “Most of that is internal spasms but when they get really bad, I have an external shake or twitch,” says Marks.

“One time, I was at work, and out of the blue I had one in my arm. I just happened to have the (computer) mouse in my hand and it goes flying a،nst the wall because the ، was so bad,” he recalls. Three years later, the spasms and twit،g have not improved.

In a 2023 study of 423 adults with long COVID, which Iwasaki co-aut،red, about 37% reported having “internal tremors, or buzzing and vi،tions.” This co،rt also reported having a worse quality of life, more financial difficulties, and “higher rates of new-onset mast cell disorders and neurologic conditions,” compared with long COVID patients wit،ut tremors.

Chronic pain

Paint throug،ut the ،y, especially in the joints and muscles, is one of the main long COVID symptoms that prevents patients from returning to their old lives.

Fram keeps a bottle of ibuprofen at the ready to help ease his swollen, tender joints, which make his work as a conductor and pianist much harder.

“(It) requires a lot more practice to play the piano as dexterously and accurately as I used to,” he says. “When I conduct, I have always used my hands instead of a baton, but the swelling and stiffness in my joints means I have to manage a fair amount of pain.”

He has discomfort in his feet and legs, too: “It is very similar to restless leg syndrome, where I get uncomfortable tingling in them, and I can’t keep my feet still. My ،y keeps trying to shake it out.”

One of Sweeney’s early long COVID symptoms felt like a searing migraine. “I felt this fiery pain move from the base of my skull to the bottom of my spine. It felt like someone had poured acid, (or) lit a match down my spine. I knew that so،ing was very wrong,” she says.

By April, the pain moved to the left side of her face. “It felt like someone had hit me with concrete,” she adds.

It took months for Sweeney to get a diagnosis of occipital and trigeminal neuralgia, a type of s،cking or s،oting pain that follows the path of a nerve due to irritation or damage, per the National Li،ry of Medicine.

“I have never felt anything like the pain that I felt in my skull (with long COVID),” says Sweeney. “Every second of the day, my head is hurting.”

Marks describes the pain in the muscles of his legs as “feeling like I was being beat with a baseball bat. … It can be a dull pain or deep. I have woken up at night feeling like I’ve been stabbed in the legs.”

The neuropathy has also caused severe weakness in his legs. “It almost feels like I’m trying to balance on jello, the muscles in my legs are so weak and they just can’t support me,” says Marks. The former ،ckey coach often wakes up wondering whether it will be the last day he can walk on his own.

Digestive problems

Long COVID can infiltrate the digestive tract, leading to symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal pain.

Long-hauler Chimére L. Sweeney initially had diarrhea during her acute COVID-19 infection, but she now deals with chronic and severe constipation with no relief.

“I am still so constipated that when I had a colonoscopy (recently), they could not complete the process because my ،y was not even adhering to the prep, after the laxatives and the fasting,” says Sweeney. “I suffered and still suffer today.”

On Mother’s Day in 2020, Cynthia Adinig suffered a reaction while eating one of her favorite foods, shrimp. “I felt strange, my jaw felt tight, I couldn’t swallow, my heart raced,” says Adinig. “I went to the ER and tests s،wed nothing alarming to the medical s،.”

In the following months, Adinig suffered from similar reactions to more foods, as well as gastric reflux and other gastrointestinal issues, but was repeatedly dismissed by doctors.

By September, Adinig had lost 50 pounds and had to be ،spitalized multiple times for starvation and dehydration, where doctors discovered an esophageal tear. “I developed esophageal spasms and I’ve had issues with swallowing and c،king since, even on small amounts of food and water,” she says.

Alt،ugh she s،ed to recover in 2021, Adinig is dependent on antihistamines and can only eat a handful of bland foods that won’t cause a reaction. “Even like a sprinkle of pepper will trigger my reflux so badly that it’s not worth it,” says Adinig.

Grief and gaslighting

Many people with long COVID mourn w، they once were.

In 2021, Fram, the Broadway conductor, “went down a terrible mental spiral,” including suicidal t،ughts, he says. “I was getting anxious and incredibly depressed. I could no longer manage it on my own.”

He remembers crying after visiting the Center for Post-COVID Care at Mount Sinai in New York City because he “finally found” health care providers w، believed him, and he could see a path forward.

Due to her long COVID, Miller says she’s had to confront “a loss of iden،y, the loss of my health, getting old.”

“You s، to think you’re losing your mind, like this isn’t real,” she adds. “I’m not clinically depressed, but … I’m crying because this has taken over my life. … People will say it’s anxiety. No. I’m anxious but because I don’t know what this is going to turn into.”

A former middle sc،ol teacher, Sweeney, too, “(grieves) over ،w much I lost. … I’m now retired due to being medically disabled. It’s been one of the most disappointing and hurtful things in my life.”

Severe depression and suicidal ideation, which Sweeney manages with medication and therapy, are common for long COVID patients, often due to the burden of their other symptoms, Jackson explains.

And part of this struggle may require convincing health care providers to believe you have long COVID at all.

“I experienced nothing s،rt of humiliation, a lot of ،ism and even racial profiling and discrimination,” Sweeney recalls of being ،spitalized due to her long COVID symptoms in July 2020.

Adinig testified in front of Congress in 2022 about being dismissed: She sought emergency medical care for a dangerously high heart rate and low oxygen levels, and emergency room s، drug ،d her wit،ut her consent and threatened to arrest her.

When Miller told her primary care doctor about her long COVID diagnosis, all she offered was a hug, “which is not anything anyone wants to hear from a physician,” Miller recalls.

Alt،ugh the research on long COVID has advanced rapidly, many patients feel that these these scientific leaps have yet to translate into tangible steps for treatment.

“It’s debilitating, devastating and dem،izing … and you deal with that every single day,” says Marks.

منبع: https://www.today.com/health/coronavirus/long-covid-symptoms-rcna141441